A Failure Pattern in Evolving Systems

Most complex systems do not fail because of a single bad decision.

They fail because of many reasonable decisions made incrementally — without an explicit model for growth.

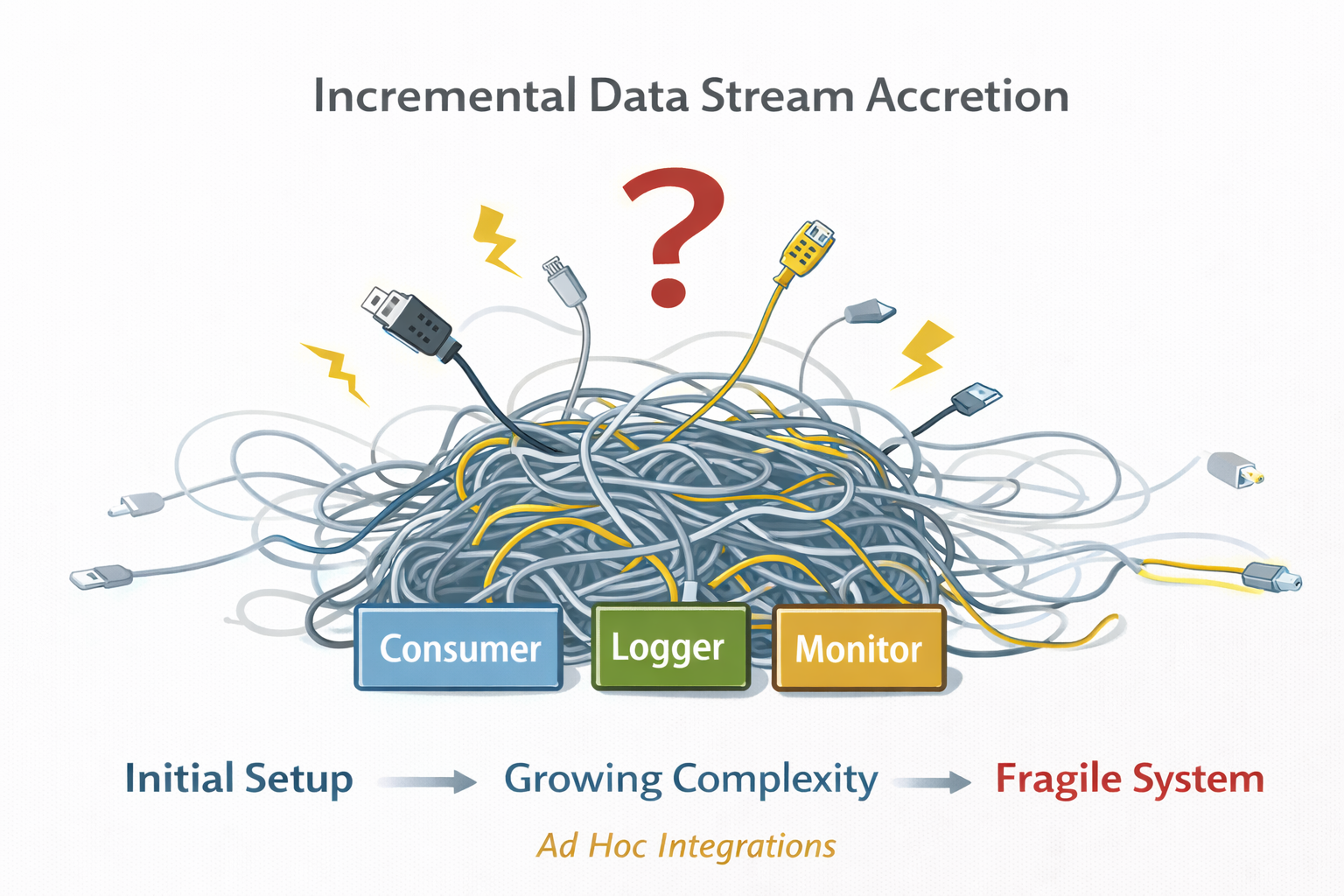

One of the most common manifestations of this is incremental data stream accretion.

The Pattern

A system starts simple.

There is:

- one data source

- one consumer

- one clear purpose

A direct connection is created. It works.

Later, another data stream is introduced:

- an additional sensor

- another robot

- another service

- another user interface

It is integrated in the same way — pragmatically, locally, “just to get it working”.

Then another stream is added.

Then logging.

Then replay.

Then remote access.

Then analytics.

At no point does the system stop to ask:

- What is a data stream in this system?

- Who owns it?

- Who is allowed to consume it?

- What assumptions exist about timing, rate, or structure?

- What happens when it disappears?

The system continues to function — until it suddenly doesn’t.

Where This Appears

This pattern is not domain-specific.

It appears in:

- XR systems integrating live sensor and state data

- Robotics systems combining perception, control, and monitoring

- Research software evolving into shared infrastructure

- Early-stage data platforms

- Internal tools that quietly become mission-critical

XR and robotics simply expose the problem earlier, because:

- timing matters

- data rates differ

- failures are immediately visible

The underlying issue exists regardless of domain.

Why Teams Fall Into It

Incremental data stream accretion is not caused by carelessness or lack of skill.

It emerges because:

- Early success hides future fragility

The first integrations genuinely work. - Architecture feels premature at small scale

Designing structure early appears unnecessary. - Responsibility is local, not systemic

Each stream is added to solve an immediate problem. - Data is treated as wiring, not as a system concept

Streams are connections, not entities with behavior and lifecycle.

Every step is rational.

The trajectory is predictable.

What Breaks First

The initial failures are rarely dramatic.

They show up as:

- undocumented timing assumptions

- fragile consumers that break on schema changes

- missing or silent data during reconnects

- debugging that depends on tribal knowledge

- hesitation to add “just one more stream”

Eventually, teams reach a point where:

Adding data becomes riskier than using it.

At that moment, development slows and confidence erodes.

Why This Is Hard to Fix Later

Once many streams exist:

- assumptions are embedded throughout the system

- semantics are implicit

- lifecycles are unclear

- consumers rely on undocumented behavior

The architecture has emerged, rather than being designed.

Refactoring becomes dangerous because:

- behavior is inferred, not specified

- small changes have wide effects

- no clear ownership exists

At this stage, “cleaning it up later” is no longer trivial.

An Illustrative Example

The following example is intentionally generic — not because it is rare, but because it is common.

A system begins with a single real-time data feed consumed by a visualization client.

Later, a second consumer is added for logging.

Then a third for remote monitoring.

Each addition works in isolation.

Over time, consumers begin to assume:

- data arrives at a certain rate

- streams are always present

- schemas do not change

When one stream temporarily disappears, parts of the system fail in unexpected ways.

At that point, it becomes clear that the issue is not the data itself — but the absence of an explicit model around it.

The Underlying Mistake

The core problem is not technical.

It is conceptual.

The system never treated data streams as first-class entities.

Instead, streams were treated as:

- pipes

- callbacks

- topics

- endpoints

Without explicit meaning, ownership, or lifecycle.

The Design Principle That Avoids This

The solution is not a specific technology or framework.

It is a shift in perspective:

Design for data growth explicitly, even when the system is small.

This means:

- defining what a stream represents

- separating transport from semantics

- making lifecycle explicit

- allowing consumers to appear and disappear

- assuming schemas and timing will evolve

Not all of this must be implemented on day one.

But it must be acknowledged as a system concern, not an implementation detail.

Why This Matters Early

Once a system reaches a certain complexity threshold, architecture can no longer be added safely.

At that point:

- structure becomes archaeology

- behavior is discovered, not designed

- change becomes disproportionately expensive

Incremental data stream accretion is dangerous precisely because it feels harmless — until it isn’t.

Closing Observation

Teams often believe their system is unique.

In practice, this failure pattern appears with remarkable consistency.

If data streams are added one by one without an explicit model, the outcome is not uncertainty —

it is a predictable trajectory.

And predictable trajectories can be designed against.

About this series

This article is part of Failure Patterns in Evolving Systems — a collection of observed patterns that emerge when systems grow under real-world constraints.