When the First Working Version Becomes Untouchable

Prototypes are built to answer questions.

They are meant to explore:

- feasibility

- constraints

- unknowns

- interactions

They are not meant to define long-term structure.

Prototype lock-in occurs when this distinction quietly disappears.

The Pattern

A prototype is created to test an idea.

It is:

- fast

- incomplete

- exploratory

- shaped by uncertainty

Its purpose is simple: does this work at all?

Then it works.

At that moment, something subtle happens.

The prototype:

- is demonstrated

- is extended

- becomes depended on

- gains users

- accumulates features

Without an explicit decision, the prototype becomes the system.

The code still runs.

The architecture does not improve.uddenly doesn’t.

Where This Appears

Prototype lock-in is not limited to software.

It appears in:

- research systems that outlive their initial experiments

- internal tools that quietly become infrastructure

- startups evolving past product–market fit

- XR and robotics systems moving from demo to deployment

- data pipelines built under early uncertainty

Any domain where learning precedes structure is susceptible.

Why Teams Fall Into It

Prototype lock-in is rarely a conscious choice.

It happens because:

- Success creates inertia

Once something works, replacing it feels risky. - Time pressure discourages re-thinking

Rebuilding looks like lost progress. - Incremental improvement feels safer than re-design

Small refactors appear sufficient. - The cost of throwing things away is emotionally visible

The cost of keeping them is deferred.

At no point does anyone say:

“This prototype is now our architecture.”

It simply becomes true.

What Breaks First

The early signs are subtle:

- Structure reflects exploration, not intent

- Modules mirror the order of discovery

- Assumptions remain implicit

- Changes require growing caution

- New contributors struggle to understand boundaries

Velocity decreases, even though functionality increases.

Eventually, the system reaches a point where:

Every change feels larger than it should.

Why Refactoring Is Not Enough

Teams often believe they can fix prototype lock-in gradually.

In practice, this rarely works.

Because:

- architectural decisions are distributed across the system

- early shortcuts are no longer isolated

- behavior depends on undocumented assumptions

Refactoring improves code quality, but not structural intent.

The system remains shaped by the questions it once tried to answer —

not the role it now plays.

An Illustrative Example

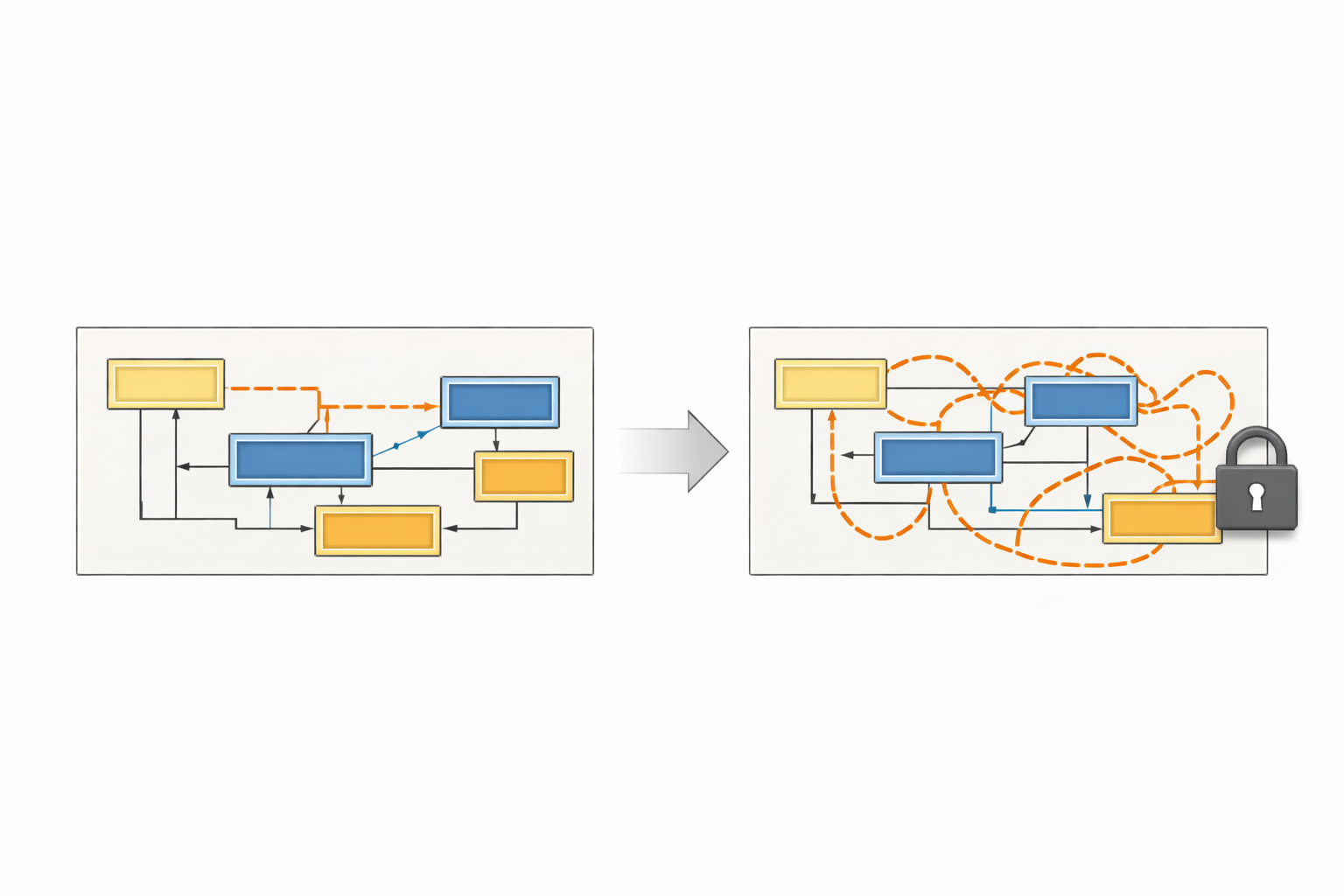

The following example is intentionally generic.

A prototype is built to connect a small set of components.

It answers its original question quickly and successfully.

Over time, additional functionality is layered onto it:

- configuration

- logging

- monitoring

- additional integrations

Each addition is reasonable.

What is never revisited is the question:

“Given what we now know, is this the structure we would design today?”

Eventually, the prototype contains the knowledge gained from experimentation —

but is still constrained by the shape of uncertainty.licit model around it.

The Underlying Mistake

The mistake is not technical.

It is temporal.

The system confuses two distinct phases:

- Exploration — where uncertainty is high

- Design — where uncertainty has collapsed

When structure is fixed during exploration, uncertainty hardens into architecture.

The Design Principle That Avoids This

The solution is not constant rewriting.

It is intentional rebuilding at the right moment.

Architecture should be designed after key uncertainties are resolved, not before.

A deliberate rebuild:

- separates learned knowledge from accidental structure

- allows decisions to be made consciously

- often increases development speed rather than reducing it

Rebuilding is not wasteful when it replaces uncertainty with intent.

Why This Matters Early

The opportunity to rebuild is time-sensitive.

Early on:

- systems are small

- assumptions are visible

- dependencies are limited

Later:

- behavior is entrenched

- risk increases

- rebuilding feels prohibitive

Prototype lock-in is dangerous because it delays this decision until it no longer feels possible.

Closing Observation

Teams often believe their system is unique.

In practice, this failure pattern appears with remarkable consistency.

If data streams are added one by one without an explicit model, the outcome is not uncertainty —

it is a predictable trajectory.

And predictable trajectories can be designed against.

About this series

This article is part of Failure Patterns in Evolving Systems — a collection of observed patterns that emerge when systems grow under real-world constraints.